A BRIEF HISTORY OF BIRD RECORDS IN SEYCHELLES

Extract from d'Avezac 1848

Seychelles was first settled in 1770. Not surprisingly, there are very few references to birds in the early literature, colonists being preoccupied with the daily struggle for survival and with the competition between the superpowers of the day on the sea route to India. The first known attempt at a list of birds appears in French in Froberville, E. de. 1848. Rodrigues, Galega, Les Sechelles, Les Almirantes, etc. In M.A.P. d'Avezac, ed.: Iles de l'Afrique 3me partie, II. Paris: Firmin Didot Freres, Editeurs, 65-114. Frustratingly vague, it nevertheless covers the more obvious resident species. These include pigeons et de tourterelles (presumably Madagascar Turtle Dove and Seychelles Blue Pigeon), perruches vertes (Seychelles Parakeet), les perroquets de Madagascar (perhaps Seychelles Black Parrot), les veuves (probably Seychelles Paradise Flycatcher), les aigrettes (Cattle Egret), les merles (Seychelles Bulbul), les cardinaux (perhaps Madagascar Fody, kardinal being sometimes used for this species), les doyoles (perhaps Seychelles Magpie Robin, dyal being one of the species' names still in use), les gobe-mouches (flycatchers, again!), colibris (sunbirds) and so on.

The first scientist to attempt a systematic list of the birds of Seychelles was Edward Newton, who visited in 1865. Newton noted a total of 42 species from the granitic islands, including the first recorded annual migrants, Grey Plover Pluvialis squatarola and Little Stint Calidris minuta. He also recorded the first vagrant, a bird of prey listed as “Falco an Circus? ‘Papangue’ said to occur in bad weather”. Perhaps this was a Black Kite or Yellow-billed Kite known in Creole as Papang? Or perhaps this term was more widely applied but without a specimen or detailed notes it is impossible to classify. Hence the need for a records committee such as SBRC, though this was still more than a century away!

The first scientist to attempt a systematic list of the birds of Seychelles was Edward Newton, who visited in 1865. Newton noted a total of 42 species from the granitic islands, including the first recorded annual migrants, Grey Plover Pluvialis squatarola and Little Stint Calidris minuta. He also recorded the first vagrant, a bird of prey listed as “Falco an Circus? ‘Papangue’ said to occur in bad weather”. Perhaps this was a Black Kite or Yellow-billed Kite known in Creole as Papang? Or perhaps this term was more widely applied but without a specimen or detailed notes it is impossible to classify. Hence the need for a records committee such as SBRC, though this was still more than a century away!

Oriental Pratincole at Bird Island. Photo: Adrian Skerrett

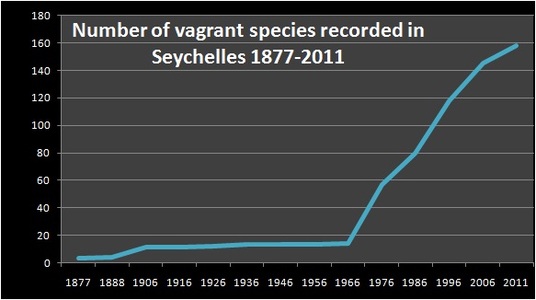

In 1877, the first vagrant species (occurring less than annually) were confirmed when Lantz collected three species, the specimens now held at the Paris Museum. One of Lantz's species, Oriental Pratincole Glareola maldivarum, was chosen as the logo for SBRC in honour of this landmark event. In 1888, JJ Lister collected a Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus at Mahe, the specimen now held at Cambridge Museum, UK. Then in 1892 the first migrants in the outer islands were recorded during the visit of W.L. Abbott. Abbott’s collection from Aldabra included five species classed as vagrants by SBRC. Two more vagrant species were added to the list by collectors in 1904 and another in 1907. Yet due to a decline in scientific interest during the turbulent first half of the 20th Century it would be nearly 60 years before the next vagrant was recorded.

Aldabra: a magnet for migrants. Photo: Mohamed Amin

Ironically, while the intervention of two World Wars may have contributed to a blank era for bird records in Seychelles, it was the fear of a Third World War that indirectly rekindled interest. Aldabra, the world's largest raised coral atoll, was identified as a possible site for a Western military base. Horrified by the threat to its unique biodiversity, Royal Society and others campaigned for the atoll to be preserved and in 1965, a research centre was established. New records of vagrant bird species inevitably followed, some photographed for the first time, details published in scientific journals or specimens collected, later enabling SBRC to confirm or correct the identifications. However, the long sea journey to seychelles meant that apart from the small number of scientists working at Aldabra, the islands remained little known and little visited.

In 1972, the opening of Seychelles International Airport made access to the islands considerably easier and reports of rare migrants began to come in. Sometimes observers would publish their sightings, sometimes not. If sightings were not published, the information was lost. Buteven when published, there was some confusion over the identity of certain species so that for example, small terns seen around the islands vwere variously described as Damara Tern, Little Tern or Saunders's Tern, but which was correct? A few people started to produce lists of sightings, but without any form of verification their accuracy remained in doubt. Even experts can (and often do!) make mistakes. Fortunately some observers kept detailed field notes, including Chris Feare, one of the founder members of SBRC and the first professional ornithologist to be based in the inner islands of Seychelles. His meticulous notes would later enable SBRC to confirm many new records adding 20 species to the Seychelles list, including 18 in 1972-1973 alone.

When SBRC was established in 1992, one of the first tasks was to gather together a wealth of historic information for assessment, including published records, details of museum specimens and field notes, sketches, photographs and so on held in private collections. For new records, a record form was designed for observers to supply supporting information to prove the identity of species seen in Seychelles. Where records are not accepted it is usually because the observer has supplied no details or too few details concerning identification. However, the vast majority of records sent to SBRC are accepted and the number of species recorded in Seychelles has rocketed. At 1 May 2012, it stands at 258 species, comprising 64 breeding species, 28 annual migrants, 158 vagrants and eight extinct species with new species recorded each year.